Kernel (computing)

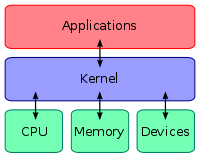

In computing, the kernel is the central component of most computer operating systems; it is a bridge between applications and the actual data processing done at the hardware level. The kernel's responsibilities include managing the system's resources (the communication between hardware and software components).[1] Usually as a basic component of an operating system, a kernel can provide the lowest-level abstraction layer for the resources (especially processors and I/O devices) that application software must control to perform its function. It typically makes these facilities available to application processes through inter-process communication mechanisms and system calls.

Operating system tasks are done differently by different kernels, depending on their design and implementation. While monolithic kernels execute all the operating system code in the same address space to increase the performance of the system, microkernels run most of the operating system services in user space as servers, aiming to improve maintainability and modularity of the operating system.[2] A range of possibilities exists between these two extremes.

Contents |

Overview

On the definition of "kernel", Jochen Liedtke said that the word is "traditionally used to denote the part of the operating system that is mandatory and common to all other software."[3] Most operating systems rely on this concept of the kernel. The existence of a kernel is a natural consequence of designing a computer system as a series of abstraction layers,[4] each relying on the functions of layers beneath it. The kernel, from this viewpoint, is simply the name given to the lowest level of abstraction that is implemented in software. In order to avoid having a kernel, one would have to design all the software on the system not to use abstraction layers; this would increase the complexity of the design to such a point that only the simplest systems could feasibly be implemented.

While it is today mostly called the kernel, originally the same part of the operating system was also called the nucleus or core[1][5][6][7], and was conceived as containing only the essential support features of the operating system. However the term core has also been used to refer to the primary memory of a computer system, because some early computers used a form of memory called core memory.

In most cases, the boot loader starts executing the kernel in supervisor mode.[8] The kernel then initializes itself and starts the first process. After this, the kernel does not typically execute directly, only in response to external events (e.g., via system calls used by applications to request services from the kernel, or via interrupts used by the hardware to notify the kernel of events). Additionally, the kernel typically provides a loop that is executed whenever no processes are available to run; this is often called the idle process.

Kernel development is considered one of the most complex and difficult tasks in programming.[9] Its central position in an operating system implies the necessity for good performance, which defines the kernel as a critical piece of software and makes its correct design and implementation difficult. For various reasons, a kernel might not even be able to use the abstraction mechanisms it provides to other software. Such reasons include memory management concerns (for example, a user-mode function might rely on memory being subject to demand paging, but as the kernel itself provides that facility it cannot use it, because then it might not remain in memory to provide that facility) and lack of reentrancy, thus making its development even more difficult for software engineers.

A kernel will usually provide features for low-level scheduling[10] of processes (dispatching), inter-process communication, process synchronization, context switching, manipulation of process control blocks, interrupt handling, process creation and destruction, and process suspension and resumption (see process states).[5][7]

Kernel basic facilities

The kernel's primary purpose is to manage the computer's resources and allow other programs to run and use these resources.[1] Typically, the resources consist of:

- The Central Processing Unit (CPU, the processor). This is the most central part of a computer system, responsible for running or executing programs on it. The kernel takes responsibility for deciding at any time which of the many running programs should be allocated to the processor or processors (each of which can usually run only one program at a time)

- The computer's memory. Memory is used to store both program instructions and data. Typically, both need to be present in memory in order for a program to execute. Often multiple programs will want access to memory, frequently demanding more memory than the computer has available. The kernel is responsible for deciding which memory each process can use, and determining what to do when not enough is available.

- Any Input/Output (I/O) devices present in the computer, such as keyboard, mouse, disk drives, printers, displays, etc. The kernel allocates requests from applications to perform I/O to an appropriate device (or subsection of a device, in the case of files on a disk or windows on a display) and provides convenient methods for using the device (typically abstracted to the point where the application does not need to know implementation details of the device).

Key aspects necessary in resource managements are the definition of an execution domain (address space) and the protection mechanism used to mediate the accesses to the resources within a domain.[1]

Kernels also usually provide methods for synchronization and communication between processes (called inter-process communication or IPC).

A kernel may implement these features itself, or rely on some of the processes it runs to provide the facilities to other processes, although in this case it must provide some means of IPC to allow processes to access the facilities provided by each other.

Finally, a kernel must provide running programs with a method to make requests to access these facilities.

Process management

The main task of a kernel is to allow the execution of applications and support them with features such as hardware abstractions. A process defines which memory portions the application can access.[11] (For this introduction, process, application and program are used as synonyms.) Kernel process management must take into account the hardware built-in equipment for memory protection.[12]

To run an application, a kernel typically sets up an address space for the application, loads the file containing the application's code into memory (perhaps via demand paging), sets up a stack for the program and branches to a given location inside the program, thus starting its execution.[13]

Multi-tasking kernels are able to give the user the illusion that the number of processes being run simultaneously on the computer is higher than the maximum number of processes the computer is physically able to run simultaneously. Typically, the number of processes a system may run simultaneously is equal to the number of CPUs installed (however this may not be the case if the processors support simultaneous multithreading).

In a pre-emptive multitasking system, the kernel will give every program a slice of time and switch from process to process so quickly that it will appear to the user as if these processes were being executed simultaneously. The kernel uses scheduling algorithms to determine which process is running next and how much time it will be given. The algorithm chosen may allow for some processes to have higher priority than others. The kernel generally also provides these processes a way to communicate; this is known as inter-process communication (IPC) and the main approaches are shared memory, message passing and remote procedure calls (see concurrent computing).

Other systems (particularly on smaller, less powerful computers) may provide co-operative multitasking, where each process is allowed to run uninterrupted until it makes a special request that tells the kernel it may switch to another process. Such requests are known as "yielding", and typically occur in response to requests for interprocess communication, or for waiting for an event to occur. Older versions of Windows and Mac OS both used co-operative multitasking but switched to pre-emptive schemes as the power of the computers to which they were targeted grew.

The operating system might also support multiprocessing (SMP or Non-Uniform Memory Access); in that case, different programs and threads may run on different processors. A kernel for such a system must be designed to be re-entrant, meaning that it may safely run two different parts of its code simultaneously. This typically means providing synchronization mechanisms (such as spinlocks) to ensure that no two processors attempt to modify the same data at the same time.

Memory management

The kernel has full access to the system's memory and must allow processes to safely access this memory as they require it. Often the first step in doing this is virtual addressing, usually achieved by paging and/or segmentation. Virtual addressing allows the kernel to make a given physical address appear to be another address, the virtual address. Virtual address spaces may be different for different processes; the memory that one process accesses at a particular (virtual) address may be different memory from what another process accesses at the same address. This allows every program to behave as if it is the only one (apart from the kernel) running and thus prevents applications from crashing each other.[13]

On many systems, a program's virtual address may refer to data which is not currently in memory. The layer of indirection provided by virtual addressing allows the operating system to use other data stores, like a hard drive, to store what would otherwise have to remain in main memory (RAM). As a result, operating systems can allow programs to use more memory than the system has physically available. When a program needs data which is not currently in RAM, the CPU signals to the kernel that this has happened, and the kernel responds by writing the contents of an inactive memory block to disk (if necessary) and replacing it with the data requested by the program. The program can then be resumed from the point where it was stopped. This scheme is generally known as demand paging.

Virtual addressing also allows creation of virtual partitions of memory in two disjointed areas, one being reserved for the kernel (kernel space) and the other for the applications (user space). The applications are not permitted by the processor to address kernel memory, thus preventing an application from damaging the running kernel. This fundamental partition of memory space has contributed much to current designs of actual general-purpose kernels and is almost universal in such systems, although some research kernels (e.g. Singularity) take other approaches.

Device management

To perform useful functions, processes need access to the peripherals connected to the computer, which are controlled by the kernel through device drivers. For example, to show the user something on the screen, an application would make a request to the kernel, which would forward the request to its display driver, which is then responsible for actually plotting the character/pixel.[13]

A kernel must maintain a list of available devices. This list may be known in advance (e.g. on an embedded system where the kernel will be rewritten if the available hardware changes), configured by the user (typical on older PCs and on systems that are not designed for personal use) or detected by the operating system at run time (normally called plug and play).

In a plug and play system, a device manager first performs a scan on different hardware buses, such as Peripheral Component Interconnect (PCI) or Universal Serial Bus (USB), to detect installed devices, then searches for the appropriate drivers.

As device management is a very OS-specific topic, these drivers are handled differently by each kind of kernel design, but in every case, the kernel has to provide the I/O to allow drivers to physically access their devices through some port or memory location. Very important decisions have to be made when designing the device management system, as in some designs accesses may involve context switches, making the operation very CPU-intensive and easily causing a significant performance overhead.

System calls

To actually perform useful work, a process must be able to access the services provided by the kernel. This is implemented differently by each kernel, but most provide a C library or an API, which in turn invokes the related kernel functions.[14]

The method of invoking the kernel function varies from kernel to kernel. If memory isolation is in use, it is impossible for a user process to call the kernel directly, because that would be a violation of the processor's access control rules. A few possibilities are:

- Using a software-simulated interrupt. This method is available on most hardware, and is therefore very common.

- Using a call gate. A call gate is a special address stored by the kernel in a list in kernel memory at a location known to the processor. When the processor detects a call to that address, it instead redirects to the target location without causing an access violation. This requires hardware support, but the hardware for it is quite common.

- Using a special system call instruction. This technique requires special hardware support, which common architectures (notably, x86) may lack. System call instructions have been added to recent models of x86 processors, however, and some operating systems for PCs make use of them when available.

- Using a memory-based queue. An application that makes large numbers of requests but does not need to wait for the result of each may add details of requests to an area of memory that the kernel periodically scans to find requests.

Kernel design decisions

Issues of kernel support for protection

An important consideration in the design of a kernel is the support it provides for protection from faults (fault tolerance) and from malicious behaviors (security). These two aspects are usually not clearly distinguished, and the adoption of this distinction in the kernel design leads to the rejection of a hierarchical structure for protection.[1]

The mechanisms or policies provided by the kernel can be classified according to several criteria, as: static (enforced at compile time) or dynamic (enforced at runtime); preemptive or post-detection; according to the protection principles they satisfy (i.e. Denning[15][16]); whether they are hardware supported or language based; whether they are more an open mechanism or a binding policy; and many more.

Fault tolerance

A useful measure of the level of fault tolerance of a system is how closely it adheres to the principle of least privilege.[17] In cases where multiple programs are running on a single computer, it is important to prevent a fault in one of the programs from negatively affecting the other. Extended to malicious design rather than a fault, this also applies to security, where it is necessary to prevent processes from accessing information without being granted permission.

The two major hardware approaches[18] for protection (of sensitive information) are Hierarchical protection domains (also called ring architectures, segment architectures or supervisor mode),[19] and Capability-based addressing.[20]

Hierarchical protection domains are much less flexible, as is the case with every kernel with a hierarchical structure assumed as global design criterion.[1] In the case of protection it is not possible to assign different privileges to processes that are at the same privileged level, and therefore is not possible to satisfy Denning's four principles for fault tolerance[15][16] (particularly the Principle of least privilege). Hierarchical protection domains also have a major performance drawback, since interaction between different levels of protection, when a process has to manipulate a data structure both in 'user mode' and 'supervisor mode', always requires message copying (transmission by value).[21] A kernel based on capabilities, however, is more flexible in assigning privileges, can satisfy Denning's fault tolerance principles,[22] and typically doesn't suffer from the performance issues of copy by value.

Both approaches typically require some hardware or firmware support to be operable and efficient. The hardware support for hierarchical protection domains[23] is typically that of "CPU modes." An efficient and simple way to provide hardware support of capabilities is to delegate the MMU the responsibility of checking access-rights for every memory access, a mechanism called capability-based addressing.[22] Most commercial computer architectures lack MMU support for capabilities. An alternative approach is to simulate capabilities using commonly-supported hierarchical domains; in this approach, each protected object must reside in an address space that the application does not have access to; the kernel also maintains a list of capabilities in such memory. When an application needs to access an object protected by a capability, it performs a system call and the kernel performs the access for it. The performance cost of address space switching limits the practicality of this approach in systems with complex interactions between objects, but it is used in current operating systems for objects that are not accessed frequently or which are not expected to perform quickly.[24][25] Approaches where protection mechanism are not firmware supported but are instead simulated at higher levels (e.g. simulating capabilities by manipulating page tables on hardware that does not have direct support), are possible, but there are performance implications.[26] Lack of hardware support may not be an issue, however, for systems that choose to use language-based protection.[27]

An important kernel design decision is the choice of the abstraction levels where the security mechanisms and policies should be implemented. Kernel security mechanisms play a critical role in supporting security at higher levels.[22][28][29][30][31]

One approach is to use firmware and kernel support for fault tolerance (see above), and build the security policy for malicious behavior on top of that (adding features such as cryptography mechanisms where necessary), delegating some responsibility to the compiler. Approaches that delegate enforcement of security policy to the compiler and/or the application level are often called language-based security.

The lack of many critical security mechanisms in current mainstream operating systems impedes the implementation of adequate security policies at the application abstraction level.[28] In fact, a common misconception in computer security is that any security policy can be implemented in an application regardless of kernel support.[28]

Hardware-based protection or language-based protection

Typical computer systems today use hardware-enforced rules about what programs are allowed to access what data. The processor monitors the execution and stops a program that violates a rule (e.g., a user process that is about to read or write to kernel memory, and so on). In systems that lack support for capabilities, processes are isolated from each other by using separate address spaces.[32] Calls from user processes into the kernel are regulated by requiring them to use one of the above-described system call methods.

An alternative approach is to use language-based protection. In a language-based protection system, the kernel will only allow code to execute that has been produced by a trusted language compiler. The language may then be designed such that it is impossible for the programmer to instruct it to do something that will violate a security requirement.[27]

Advantages of this approach include:

- No need for separate address spaces. Switching between address spaces is a slow operation that causes a great deal of overhead, and a lot of optimization work is currently performed in order to prevent unnecessary switches in current operating systems. Switching is completely unnecessary in a language-based protection system, as all code can safely operate in the same address space.

- Flexibility. Any protection scheme that can be designed to be expressed via a programming language can be implemented using this method. Changes to the protection scheme (e.g. from a hierarchical system to a capability-based one) do not require new hardware.

Disadvantages include:

- Longer application start up time. Applications must be verified when they are started to ensure they have been compiled by the correct compiler, or may need recompiling either from source code or from bytecode.

- Inflexible type systems. On traditional systems, applications frequently perform operations that are not type safe. Such operations cannot be permitted in a language-based protection system, which means that applications may need to be rewritten and may, in some cases, lose performance.

Examples of systems with language-based protection include JX and Microsoft's Singularity.

Process cooperation

Edsger Dijkstra proved that from a logical point of view, atomic lock and unlock operations operating on binary semaphores are sufficient primitives to express any functionality of process cooperation.[33] However this approach is generally held to be lacking in terms of safety and efficiency, whereas a message passing approach is more flexible.[7]

I/O devices management

The idea of a kernel where I/O devices are handled uniformly with other processes, as parallel co-operating processes, was first proposed and implemented by Brinch Hansen (although similar ideas were suggested in 1967[34][35]). In Hansen's description of this, the "common" processes are called internal processes, while the I/O devices are called external processes.[7]

Kernel-wide design approaches

Naturally, the above listed tasks and features can be provided in many ways that differ from each other in design and implementation.

The principle of separation of mechanism and policy is the substantial difference between the philosophy of micro and monolithic kernels.[36][37] Here a mechanism is the support that allows the implementation of many different policies, while a policy is a particular "mode of operation". For instance, a mechanism may provide for user log-in attempts to call an authorization server to determine whether access should be granted; a policy may be for the authorization server to request a password and check it against an encrypted password stored in a database. Because the mechanism is generic, the policy could more easily be changed (e.g. by requiring the use of a security token) than if the mechanism and policy were integrated in the same module.

In minimal microkernel just some very basic policies are included,[37] and its mechanisms allows what is running on top of the kernel (the remaining part of the operating system and the other applications) to decide which policies to adopt (as memory management, high level process scheduling, file system management, etc.).[1][7] A monolithic kernel instead tends to include many policies, therefore restricting the rest of the system to rely on them.

Per Brinch Hansen presented cogent arguments in favor of separation of mechanism and policy.[1][7] The failure to properly fulfill this separation, is one of the major causes of the lack of substantial innovation in existing operating systems,[1] a problem common in computer architecture.[38][39][40] The monolithic design is induced by the "kernel mode"/"user mode" architectural approach to protection (technically called hierarchical protection domains), which is common in conventional commercial systems;[41] in fact, every module needing protection is therefore preferably included into the kernel.[41] This link between monolithic design and "privileged mode" can be reconducted to the key issue of mechanism-policy separation;[1] in fact the "privileged mode" architectural approach melts together the protection mechanism with the security policies, while the major alternative architectural approach, capability-based addressing, clearly distinguishes between the two, leading naturally to a microkernel design[1] (see Separation of protection and security).

While monolithic kernels execute all of their code in the same address space (kernel space) microkernels try to run most of their services in user space, aiming to improve maintainability and modularity of the codebase.[2] Most kernels do not fit exactly into one of these categories, but are rather found in between these two designs. These are called hybrid kernels. More exotic designs such as nanokernels and exokernels are available, but are seldom used for production systems. The Xen hypervisor, for example, is an exokernel.

Monolithic kernels

In a monolithic kernel, all OS services run along with the main kernel thread, thus also residing in the same memory area. This approach provides rich and powerful hardware access. Some developers, such as UNIX developer Ken Thompson, maintain that it is "easier to implement a monolithic kernel"[42] than microkernels. The main disadvantages of monolithic kernels are the dependencies between system components — a bug in a device driver might crash the entire system — and the fact that large kernels can become very difficult to maintain.

Microkernels

The microkernel approach consists of defining a simple abstraction over the hardware, with a set of primitives or system calls to implement minimal OS services such as memory management, multitasking, and inter-process communication. Other services, including those normally provided by the kernel, such as networking, are implemented in user-space programs, referred to as servers. Microkernels are easier to maintain than monolithic kernels, but the large number of system calls and context switches might slow down the system because they typically generate more overhead than plain function calls.

A microkernel allows the implementation of the remaining part of the operating system as a normal application program written in a high-level language, and the use of different operating systems on top of the same unchanged kernel.[7] It is also possible to dynamically switch among operating systems and to have more than one active simultaneously.[7]

Monolithic kernels vs microkernels

As the computer kernel grows, a number of problems become evident. One of the most obvious is that the memory footprint increases. This is mitigated to some degree by perfecting the virtual memory system, but not all computer architectures have virtual memory support.[43] To reduce the kernel's footprint, extensive editing has to be performed to carefully remove unneeded code, which can be very difficult with non-obvious interdependencies between parts of a kernel with millions of lines of code.

By the early 1990s, due to the various shortcomings of monolithic kernels versus microkernels, monolithic kernels were considered obsolete by virtually all operating system researchers. As a result, the design of Linux as a monolithic kernel rather than a microkernel was the topic of a famous flame war between Linus Torvalds and Andrew Tanenbaum.[44] There is merit on both sides of the argument presented in the Tanenbaum–Torvalds debate.

Performances

Monolithic kernels are designed to have all of their code in the same address space (kernel space), which some developers argue is necessary to increase the performance of the system.[45] Some developers also maintain that monolithic systems are extremely efficient if well-written.[45] The monolithic model tends to be more efficient through the use of shared kernel memory, rather than the slower IPC system of microkernel designs, which is typically based on message passing.

The performance of microkernels constructed in the 1980s and early 1990s was poor.[3][46] Studies that empirically measured the performance of these microkernels did not analyze the reasons of such inefficiency.[3] The explanations of this data were left to "folklore", with the assumption that they were due to the increased frequency of switches from "kernel-mode" to "user-mode",[3] to the increased frequency of inter-process communication[3] and to the increased frequency of context switches.[3]

In fact, as guessed in 1995, the reasons for the poor performance of microkernels might as well have been: (1) an actual inefficiency of the whole microkernel approach, (2) the particular concepts implemented in those microkernels, and (3) the particular implementation of those concepts.[3] Therefore it remained to be studied if the solution to build an efficient microkernel was, unlike previous attempts, to apply the correct construction techniques.[3]

On the other end, the hierarchical protection domains architecture that leads to the design of a monolithic kernel[41] has a significant performance drawback each time there's an interaction between different levels of protection (i.e. when a process has to manipulate a data structure both in 'user mode' and 'supervisor mode'), since this requires message copying by value.[21]

By the mid-1990s, most researchers had abandoned the belief that careful tuning could reduce this overhead dramatically, but recently, newer microkernels, optimized for performance, such as L4[47] and K42 have addressed these problems.

Hybrid kernels

Hybrid kernels are a compromise between the monolithic and microkernel designs. This implies running some services (such as the network stack or the filesystem) in kernel space to reduce the performance overhead of a traditional microkernel, but still running kernel code (such as device drivers) as servers in user space.

Nanokernels

A nanokernel delegates virtually all services — including even the most basic ones like interrupt controllers or the timer — to device drivers to make the kernel memory requirement even smaller than a traditional microkernel.[48]

Exokernels

An exokernel is a type of kernel that does not abstract hardware into theoretical models. Instead it allocates physical hardware resources, such as processor time, memory pages, and disk blocks, to different programs. A program running on an exokernel can link to a library operating system that uses the exokernel to simulate the abstractions of a well-known OS, or it can develop application-specific abstractions for better performance.[49]

History of kernel development

Early operating system kernels

Strictly speaking, an operating system (and thus, a kernel) is not required to run a computer. Programs can be directly loaded and executed on the "bare metal" machine, provided that the authors of those programs are willing to work without any hardware abstraction or operating system support. Most early computers operated this way during the 1950s and early 1960s, which were reset and reloaded between the execution of different programs. Eventually, small ancillary programs such as program loaders and debuggers were left in memory between runs, or loaded from ROM. As these were developed, they formed the basis of what became early operating system kernels. The "bare metal" approach is still used today on some video game consoles and embedded systems, but in general, newer computers use modern operating systems and kernels.

In 1969 the RC 4000 Multiprogramming System introduced the system design philosophy of a small nucleus "upon which operating systems for different purposes could be built in an orderly manner",[50] what would be called the microkernel approach.

Time-sharing operating systems

In the decade preceding Unix, computers had grown enormously in power — to the point where computer operators were looking for new ways to get people to use the spare time on their machines. One of the major developments during this era was time-sharing, whereby a number of users would get small slices of computer time, at a rate at which it appeared they were each connected to their own, slower, machine.[51]

The development of time-sharing systems led to a number of problems. One was that users, particularly at universities where the systems were being developed, seemed to want to hack the system to get more CPU time. For this reason, security and access control became a major focus of the Multics project in 1965.[52] Another ongoing issue was properly handling computing resources: users spent most of their time staring at the screen and thinking instead of actually using the resources of the computer, and a time-sharing system should give the CPU time to an active user during these periods. Finally, the systems typically offered a memory hierarchy several layers deep, and partitioning this expensive resource led to major developments in virtual memory systems.

Amiga

The Commodore Amiga was released in 1985, and was among the first (and certainly most successful) home computers to feature a microkernel operating system. The Amiga's kernel, exec.library, was small but capable, providing fast pre-emptive multitasking on hardware similar to the cooperatively-multitasked Apple Macintosh, and an advanced dynamic linking system that allowed for easy expansion.[53]

Unix

During the design phase of Unix, programmers decided to model every high-level device as a file, because they believed the purpose of computation was data transformation.[54] For instance, printers were represented as a "file" at a known location — when data was copied to the file, it printed out. Other systems, to provide a similar functionality, tended to virtualize devices at a lower level — that is, both devices and files would be instances of some lower level concept. Virtualizing the system at the file level allowed users to manipulate the entire system using their existing file management utilities and concepts, dramatically simplifying operation. As an extension of the same paradigm, Unix allows programmers to manipulate files using a series of small programs, using the concept of pipes, which allowed users to complete operations in stages, feeding a file through a chain of single-purpose tools. Although the end result was the same, using smaller programs in this way dramatically increased flexibility as well as ease of development and use, allowing the user to modify their workflow by adding or removing a program from the chain.

In the Unix model, the Operating System consists of two parts; first, the huge collection of utility programs that drive most operations, the other the kernel that runs the programs.[54] Under Unix, from a programming standpoint, the distinction between the two is fairly thin; the kernel is a program, running in supervisor mode,[8] that acts as a program loader and supervisor for the small utility programs making up the rest of the system, and to provide locking and I/O services for these programs; beyond that, the kernel didn't intervene at all in user space.

Over the years the computing model changed, and Unix's treatment of everything as a file or byte stream no longer was as universally applicable as it was before. Although a terminal could be treated as a file or a byte stream, which is printed to or read from, the same did not seem to be true for a graphical user interface. Networking posed another problem. Even if network communication can be compared to file access, the low-level packet-oriented architecture dealt with discrete chunks of data and not with whole files. As the capability of computers grew, Unix became increasingly cluttered with code. While kernels might have had 100,000 lines of code in the seventies and eighties, kernels of modern Unix successors like Linux have more than 13 million lines.[55]

Modern Unix-derivatives are generally based on module-loading monolithic kernels. Examples of this are the Linux kernel in its many distributions as well as the Berkeley software distribution variant kernels such as FreeBSD, DragonflyBSD, OpenBSD and NetBSD. Apart from these alternatives, amateur developers maintain an active operating system development community, populated by self-written hobby kernels which mostly end up sharing many features with Linux, FreeBSD, DragonflyBSD, OpenBSD or NetBSD kernels and/or being compatible with them.[56]

Mac OS

Apple Computer first launched Mac OS in 1984, bundled with its Apple Macintosh personal computer. For the first few releases, Mac OS (or System Software, as it was called) lacked many essential features, such as multitasking and a hierarchical filesystem. With time, the OS evolved and eventually became Mac OS 9 and had many new features added, but the kernel basically stayed the same. Against this, Mac OS X is based on Darwin, which uses a hybrid kernel called XNU, which was created combining the 4.3BSD kernel and the Mach kernel.[57]

Microsoft Windows

Microsoft Windows was first released in 1985 as an add-on to MS-DOS. Because of its dependence on another operating system, initial releases of Windows, prior to Windows 95, were considered an operating environment (do not confuse with operating system). This product line continued to evolve through the 1980s and 1990s, culminating with release of the Windows 9x series (upgrading the system's capabilities to 32-bit addressing and pre-emptive multitasking) through the mid 1990s and ending with the release of Windows Me in 2000. Microsoft also developed Windows NT, an operating system intended for high-end and business users. This line started with the release of Windows NT 3.1 in 1993, and has continued through the years of 2000 with Windows Vista and Windows Server 2008.

The release of Windows XP in October 2001 brought these two product lines together, with the intent of combining the stability of the NT kernel with consumer features from the 9x series.[58] The architecture of Windows NT's kernel is considered a hybrid kernel because the kernel itself contains tasks such as the Window Manager and the IPC Manager, but several subsystems run in user mode.[59] The precise breakdown of user mode and kernel mode components has changed from release to release, but with the introduction of the User Mode Driver Framework in Windows Vista, and user-mode thread scheduling in Windows 7,[60] have brought more kernel-mode functionality into user-mode processes.

Development of microkernels

Although Mach, developed at Carnegie Mellon University from 1985 to 1994, is the best-known general-purpose microkernel, other microkernels have been developed with more specific aims. The L4 microkernel family (mainly the L3 and the L4 kernel) was created to demonstrate that microkernels are not necessarily slow.[47] Newer implementations such as Fiasco and Pistachio are able to run Linux next to other L4 processes in separate address spaces.[61][62]

QNX is a real-time operating system with a minimalistic microkernel design that has been developed since 1982, having been far more successful than Mach in achieving the goals of the microkernel paradigm.[63] It is principally used in embedded systems and in situations where software is not allowed to fail, such as the robotic arms on the space shuttle and machines that control grinding of glass to extremely fine tolerances, where a tiny mistake may cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

See also

- Comparison of kernels

- Compiler

- Device Driver

- Input/output (I/O)

- Interrupt request (IRQ)

- Memory

- Random access memory

- Virtual memory

- Paging, Segmentation

- Swap space

- User space

- Memory management unit

- Multitasking

- Operating system

- Trap (computing)

Notes

For notes referring to sources, see bibliography below.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Wulf 74 pp.337-345

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Roch 2004

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Liedtke 95

- ↑ Tanenbaum 79, chapter 1

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Deitel 82, p.65-66 cap. 3.9

- ↑ Lorin 81 pp.161-186, Schroeder 77, Shaw 75 pp.245-267

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Brinch Hansen 70 pp.238-241

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 The highest privilege level has various names throughout different architectures, such as supervisor mode, kernel mode, CPL0, DPL0, Ring 0, etc. See Ring (computer security) for more information.

- ↑ Bona Fide OS Development - Bran's Kernel Development Tutorial, by Brandon Friesen

- ↑ For low-level scheduling see Deitel 82, ch. 10, pp. 249–268.

- ↑ Levy 1984, p.5

- ↑ Needham, R.M., Wilkes, M. V. Domains of protection and the management of processes, Computer Journal, vol. 17, no. 2, May 1974, pp 117-120.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Silberschatz 1990

- ↑ Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (2008). Modern Operating Systems (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 50–51. ISBN 0-13-600663-9. ". . . nearly all system calls [are] invoked from C programs by calling a library procedure . . . The library procedure . . . executes a TRAP instruction to switch from user mode to kernel mode and start execution . . ."

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Denning 1976

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Swift 2005, p.29 quote: "isolation, resource control, decision verification (checking), and error recovery."

- ↑ Cook, D.J. Measuring memory protection, accepted for 3rd International Conference on Software Engineering, Atlanta, Georgia, May 1978.

- ↑ Swift 2005 p.26

- ↑ Intel Corporation 2002

- ↑ Houdek et al. 1981

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Hansen 73, section 7.3 p.233 "interactions between different levels of protection require transmission of messages by value"

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Linden 76

- ↑ Schroeder 72

- ↑ Stephane Eranian & David Mosberger, Virtual Memory in the IA-64 Linux Kernel, Prentice Hall PTR, 2002

- ↑ Silberschatz & Galvin, Operating System Concepts, 4th ed, pp445 & 446

- ↑ Hoch, Charles; J. C. Browne (University of Texas, Austin) (July 1980). "An implementation of capabilities on the PDP-11/45" (PDF). ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review 14 (3): 22–32. doi:10.1145/850697.850701. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=850701&dl=acm&coll=&CFID=15151515&CFTOKEN=6184618. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 A Language-Based Approach to Security, Schneider F., Morrissett G. (Cornell University) and Harper R. (Carnegie Mellon University)

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 P. A. Loscocco, S. D. Smalley, P. A. Muckelbauer, R. C. Taylor, S. J. Turner, and J. F. Farrell. The Inevitability of Failure: The Flawed Assumption of Security in Modern Computing Environments. In Proceedings of the 21st National Information Systems Security Conference, pages 303–314, Oct. 1998. [1].

- ↑ J. Lepreau et al. The Persistent Relevance of the Local Operating System to Global Applications. Proceedings of the 7th ACM SIGOPS Eurcshelf/book001/book001.html Information Security: An Integrated Collection of Essays], IEEE Comp. 1995.

- ↑ J. Anderson, Computer Security Technology Planning Study, Air Force Elect. Systems Div., ESD-TR-73-51, October 1972.

- ↑ * Jerry H. Saltzer, Mike D. Schroeder (September 1975). "The protection of information in computer systems". Proceedings of the IEEE 63 (9): 1278–1308. doi:10.1109/PROC.1975.9939. http://web.mit.edu/Saltzer/www/publications/protection/.

- ↑ Jonathan S. Shapiro; Jonathan M. Smith; David J. Farber. "EROS: a fast capability system". Proceedings of the seventeenth ACM symposium on Operating systems principles. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=319151.319163.

- ↑ Dijkstra, E. W. Cooperating Sequential Processes. Math. Dep., Technological U., Eindhoven, Sept. 1965.

- ↑ "SHARER, a time sharing system for the CDC 6600". http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=363778&dl=ACM&coll=GUIDE&CFID=11111111&CFTOKEN=2222222. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ "Dynamic Supervisors - their design and construction". http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=811675&dl=ACM&coll=GUIDE&CFID=11111111&CFTOKEN=2222222. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Baiardi 1988

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Levin 75

- ↑ Denning 1980

- ↑ Jürgen Nehmer The Immortality of Operating Systems, or: Is Research in Operating Systems still Justified? Lecture Notes In Computer Science; Vol. 563. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Operating Systems of the 90s and Beyond. pp. 77 - 83 (1991) ISBN 3-540-54987-0 [2] quote: "The past 25 years have shown that research on operating system architecture had a minor effect on existing main stream systems." [3]

- ↑ Levy 84, p.1 quote: "Although the complexity of computer applications increases yearly, the underlying hardware architecture for applications has remained unchanged for decades."

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Levy 84, p.1 quote: "Conventional architectures support a single privileged mode of operation. This structure leads to monolithic design; any module needing protection must be part of the single operating system kernel. If, instead, any module could execute within a protected domain, systems could be built as a collection of independent modules extensible by any user."

- ↑ Open Sources: Voices from the Open Source Revolution

- ↑ Virtual addressing is most commonly achieved through a built-in memory management unit.

- ↑ Recordings of the debate between Torvalds and Tanenbaum can be found at dina.dk, groups.google.com, oreilly.com and Andrew Tanenbaum's website

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Matthew Russell. "What Is Darwin (and How It Powers Mac OS X)". O'Reilly Media. http://oreilly.com/pub/a/mac/2005/09/27/what-is-darwin.html?page=2. quote: "The tightly coupled nature of a monolithic kernel allows it to make very efficient use of the underlying hardware [...] Microkernels, on the other hand, run a lot more of the core processes in userland. [...] Unfortunately, these benefits come at the cost of the microkernel having to pass a lot of information in and out of the kernel space through a process known as a context switch. Context switches introduce considerable overhead and therefore result in a performance penalty." This statements are not part of a peer reviewed article.

- ↑ Härtig 97

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 The L4 microkernel family - Overview

- ↑ KeyKOS Nanokernel Architecture

- ↑ MIT Exokernel Operating System

- ↑ Hansen 2001 (os), pp.17-18

- ↑ BSTJ version of C.ACM Unix paper

- ↑ Introduction and Overview of the Multics System, by F. J. Corbató and V. A. Vissotsky.

- ↑ Sheldon Leemon. "What makes it so great! (Commodore Amiga)". Creative Computing. http://www.atarimagazines.com/creative/v11n9/34_What_makes_it_so_great.php. Retrieved 2006-02-05.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 The UNIX System — The Single Unix Specification

- ↑ Linux Kernel 2.6: It's Worth More!, by David A. Wheeler, October 12, 2004

- ↑ This community mostly gathers at Bona Fide OS Development, The Mega-Tokyo Message Board and other operating system enthusiast web sites.

- ↑ XNU: The Kernel

- ↑ LinuxWorld IDC: Consolidation of Windows won't happen

- ↑ Windows History: Windows Desktop Products History

- ↑ Holwerda, Thom (February 7, 2009). "Windows 7 Gets User Mode Scheduling". OSNews. http://www.osnews.com/story/20931/Windows_7_Gets_User_Mode_Scheduling. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ The Fiasco microkernel - Overview

- ↑ L4Ka - The L4 microkernel family and friends

- ↑ QNX Realtime Operating System Overview

References

- Roch, Benjamin (2004). "Monolithic kernel vs. Microkernel" (PDF). http://www.vmars.tuwien.ac.at/courses/akti12/journal/04ss/article_04ss_Roch.pdf. Retrieved 2006-10-12.

- Silberschatz, Abraham; James L. Peterson, Peter B. Galvin (1991). Operating system concepts. Boston, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. p. 696. ISBN 0-201-51379-X. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=95329&dl=acm&coll=&CFID=15151515&CFTOKEN=6184618.

- Deitel, Harvey M. (1984) [1982]. An introduction to operating systems (revisited first ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 673. ISBN 0-201-14502-2. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=79046&dl=GUIDE&coll=GUIDE.

- Denning, Peter J. (December 1976). "Fault tolerant operating systems". ACM Computing Surveys 8 (4): 359–389. doi:10.1145/356678.356680. ISSN 0360-0300. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=356680&dl=ACM&coll=&CFID=15151515&CFTOKEN=6184618.

- Denning, Peter J. (April 1980). "Why not innovations in computer architecture?". ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News 8 (2): 4–7. doi:10.1145/859504.859506. ISSN 0163-5964. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=859506&coll=&dl=ACM&CFID=15151515&CFTOKEN=6184618.

- Hansen, Per Brinch (April 1970). "The nucleus of a Multiprogramming System". Communications of the ACM 13 (4): 238–241. doi:10.1145/362258.362278. ISSN 0001-0782. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=362278&dl=ACM&coll=GUIDE&CFID=11111111&CFTOKEN=2222222.

- Hansen, Per Brinch (1973). Operating System Principles. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. p. 496. ISBN 0-13-637843-9. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=540365.

- Hansen, Per Brinch (2001) (PDF). The evolution of operating systems. http://brinch-hansen.net/papers/2001b.pdf. Retrieved 2006-10-24. included in book: Per Brinch Hansen, ed (2001). "1". Classic operating systems: from batch processing to distributed systems. New York,: Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–36. ISBN 0-387-95113-X. http://brinch-hansen.net/papers/2001b.pdf.

- Hermann Härtig, Michael Hohmuth, Jochen Liedtke, Sebastian Schönberg, Jean Wolter The performance of μ-kernel-based systems, "The performance of μ-kernel-based systems". Doi.acm.org. http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/268998.266660. Retrieved 2010-06-19. ACM SIGOPS Operating Systems Review, v.31 n.5, p. 66-77, Dec. 1997

- Houdek, M. E., Soltis, F. G., and Hoffman, R. L. 1981. IBM System/38 support for capability-based addressing. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM International Symposium on Computer Architecture. ACM/IEEE, pp. 341–348.

- Intel Corporation (2002) The IA-32 Architecture Software Developer’s Manual, Volume 1: Basic Architecture

- Levin, R.; E. Cohen, W. Corwin, F. Pollack, William Wulf (1975). "Policy/mechanism separation in Hydra". ACM Symposium on Operating Systems Principles / Proceedings of the fifth ACM symposium on Operating systems principles: 132–140. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=806531&dl=ACM&coll=&CFID=15151515&CFTOKEN=6184618.

- Levy, Henry M. (1984). Capability-based computer systems. Maynard, Mass: Digital Press. ISBN 0-932376-22-3. http://www.cs.washington.edu/homes/levy/capabook/index.html.

- Liedtke, Jochen. On µ-Kernel Construction, Proc. 15th ACM Symposium on Operating System Principles (SOSP), December 1995

- Linden, Theodore A. (December 1976). "Operating System Structures to Support Security and Reliable Software". ACM Computing Surveys 8 (4): 409–445. doi:10.1145/356678.356682. ISSN 0360-0300. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=356682&coll=&dl=ACM&CFID=15151515&CFTOKEN=6184618., "Operating System Structures to Support Security and Reliable Software" (PDF). http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/history/lind76.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- Lorin, Harold (1981). Operating systems. Boston, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley. pp. 161–186. ISBN 0-201-14464-6. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=578308&coll=GUIDE&dl=GUIDE&CFID=2651732&CFTOKEN=19681373.

- Schroeder, Michael D.; Jerome H. Saltzer (March 1972). "A hardware architecture for implementing protection rings". Communications of the ACM 15 (3): 157–170. doi:10.1145/361268.361275. ISSN 0001-0782. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=361275&dl=ACM&coll=&CFID=15151515&CFTOKEN=6184618.

- Shaw, Alan C. (1974). The logical design of Operating systems. Prentice-Hall. p. 304. ISBN 0-13-540112-7. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=540329.

- Tanenbaum, Andrew S. (1979). Structured Computer Organization. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-148521-0.

- Wulf, W.; E. Cohen, W. Corwin, A. Jones, R. Levin, C. Pierson, F. Pollack (June 1974). "HYDRA: the kernel of a multiprocessor operating system". Communications of the ACM 17 (6): 337–345. doi:10.1145/355616.364017. ISSN 0001-0782. http://www.cs.virginia.edu/papers/p337-wulf.pdf.

- Baiardi, F.; A. Tomasi, M. Vanneschi (1988) (in Italian). Architettura dei Sistemi di Elaborazione, volume 1. Franco Angeli. ISBN 88-204-2746-X. http://www.pangloss.it/libro.php?isbn=882042746X&id=4357&PHPSESSID=9da1895b18ed1cda115cf1c7ace9bdf0.

- Swift, Michael M; Brian N. Bershad , Henry M. Levy, Improving the reliability of commodity operating systems, "Improving the reliability of commodity operating systems". Doi.acm.org. doi:10.1002/spe.4380201404. http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/1047915.1047919. Retrieved 2010-06-19. ACM Transactions on Computer Systems (TOCS), v.23 n.1, p. 77-110, February 2005

Further reading

- Andrew Tanenbaum, Operating Systems - Design and Implementation (Third edition);

- Andrew Tanenbaum, Modern Operating Systems (Second edition);

- Daniel P. Bovet, Marco Cesati, The Linux Kernel;

- David A. Peterson, Nitin Indurkhya, Patterson, Computer Organization and Design, Morgan Koffman (ISBN 1-55860-428-6);

- B.S. Chalk, Computer Organisation and Architecture, Macmillan P.(ISBN 0-333-64551-0).

External links

- KERNEL.ORG, official Linux kernel home..

- Operating System Kernels at SourceForge.

- Operating System Kernels at Freshmeat.

- MIT Exokernel Operating System.

- Kernel image - Debian Wiki.

- The KeyKOS Nanokernel Architecture, a 1992 paper by Norman Hardy et al..

- An Overview of the NetWare Operating System, a 1994 paper by Drew Major, Greg Minshall, and Kyle Powell (primary architects behind the NetWare OS).

- Kernelnewbies, a community for learning Linux kernel hacking.

- Detailed comparison between most popular operating system kernels.